Neuroscience Exploring the Brain - Part one - Chapter 1

Published:

The first chapter of Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain provides an overview of the history, key concepts, and modern advancements in neuroscience. It traces the study of the brain from ancient Greek and Roman perspectives, through Renaissance and 19th-century discoveries, to the rise of modern neuroscience as an interdisciplinary field. Key milestones include the understanding of nerves as electrical conductors, the localization of brain functions, Darwin’s evolutionary insights, and the identification of neurons as fundamental units of the nervous system. The chapter also discusses contemporary neuroscience, which spans molecular, cellular, systems, behavioral, and cognitive levels of analysis. The role of neuroscientists, the scientific process, and the ethical considerations surrounding animal research are explored. Finally, the chapter highlights the devastating impact of neurological and psychiatric disorders, emphasizing the importance of neuroscience research in developing treatments and advancing our understanding of the brain.

Chapter 1: Neuroscience: Past, Present, and Future

INTRODUCTION

Neuroscience seeks to unravel fundamental mysteries about human perception, sensation, movement, cognition, memory, and emotions. Although the term “neuroscience” is relatively new, emerging in the 20th century, the study of the brain dates back to the origins of science. Historically, researchers from various fields—medicine, biology, psychology, physics, chemistry, and mathematics—contributed to the understanding of the nervous system. The modern neuroscience revolution began when scientists adopted an interdisciplinary approach, merging different perspectives to develop a comprehensive understanding of the brain.

The Society for Neuroscience, founded in 1970, has since become one of the largest and fastest-growing scientific organizations. Neuroscience is a broad and integrative field, requiring knowledge from molecular structures to complex behaviors. This book takes a wide-ranging perspective, exploring historical views on the brain, modern neuroscientists, and their research methods. The journey begins with an overview of neuroscience, its evolution, and the scientists who shape the field today.

THE ORIGINS OF NEUROSCIENCE

Views of the Brain in Ancient Greece

Different body parts look different because they serve different purposes. For instance, feet and hands are structured differently because they have different functions - feet are for walking, and hands are for handling objects. This suggests that how something looks is related to what it does. Observations of the head and simple tests like closing your eyes indicate that it’s specialized for sensing the environment through the eyes, ears, nose, and tongue. Ancient Greek scholars like Hippocrates believed the brain was for sensation and intelligence, while Aristotle thought the heart was the center of intellect and the brain cooled overheated blood.

Views of the Brain During the Roman Empire

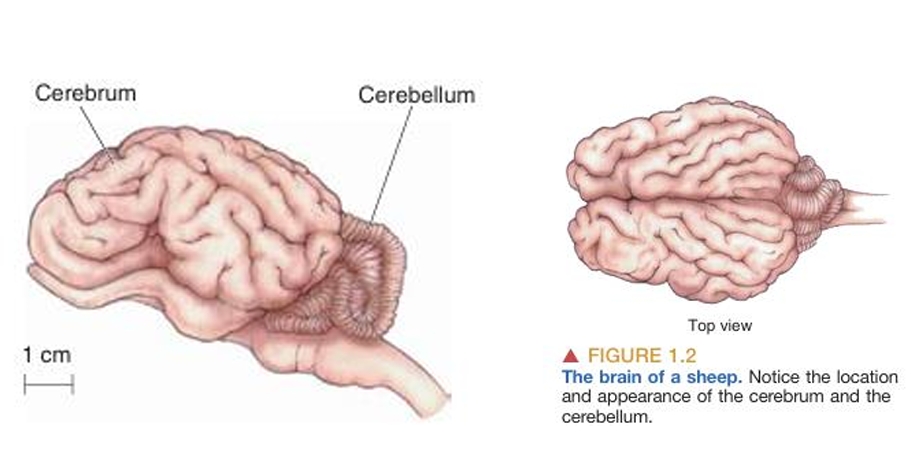

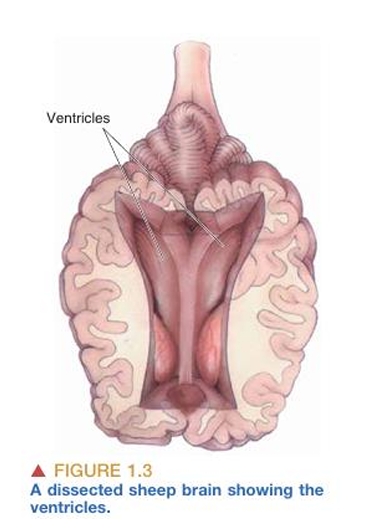

The influential Roman physician Galen, heavily influenced by the Hippocratic view of brain function, conducted animal dissections to understand brain structure and function. His observations led him to conclude that the cerebrum processes sensations while the cerebellum controls muscles, reasoning from their differing textures. Despite some inaccuracies, such as the belief in hollow brain ventricles and the influence of humors, Galen’s deductions regarding the cerebrum’s role in sensation and memory, and the cerebellum’s role in movement, were remarkably close to the truth. His work illustrates instances where correct conclusions were drawn for incorrect reasons, a common theme in the history of neuroscience.

Views of the Brain from the Renaissance to the Nineteenth Century

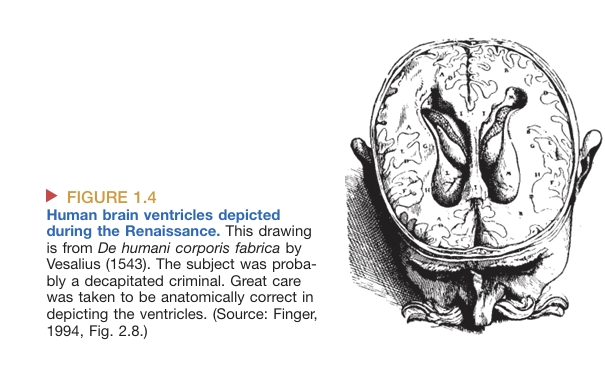

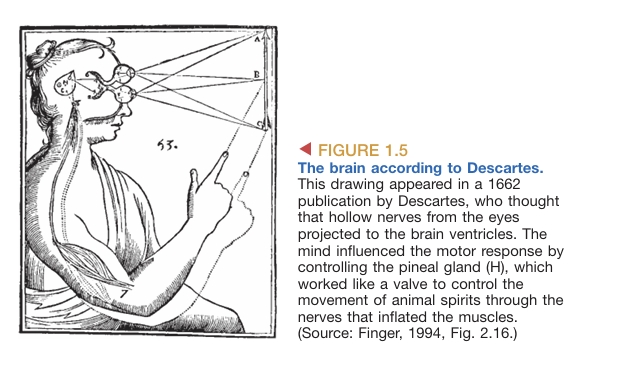

Galen’s understanding of the brain remained dominant for about 1500 years until the Renaissance, when Andreas Vesalius added more detail to brain structure. However, the ventricular theory of brain function persisted, supported by hydraulic mechanical devices in the early 17th century. René Descartes, a proponent of this theory, believed the brain controlled basic animal-like behaviors, while human intellect and soul resided outside the brain in the “mind.”

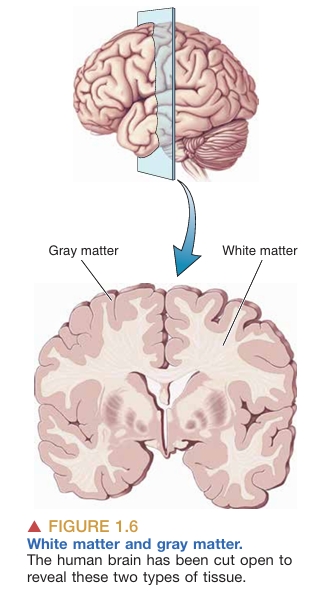

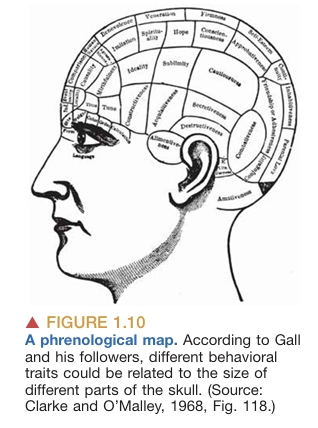

Meanwhile, other scientists began to break from traditional views, examining brain substance more closely. They identified gray and white matter, with white matter containing fibers that transmit information to and from gray matter. By the late 18th century, the nervous system’s gross anatomy was fully understood, distinguishing central (brain and spinal cord) and peripheral divisions (nerves throughout the body). Observations of consistent surface patterns on the brain led to the idea of localized functions in different brain regions, paving the way for the study of cerebral localization.

Nineteenth-Century Views of the Brain

By the end of the eighteenth century, several key understandings about the nervous system were established:

- Brain injuries can disrupt sensations, movements, and thoughts, and can even be fatal.

- The brain communicates with the body through nerves.

- Different parts of the brain likely perform different functions.

- The brain operates akin to a machine, adhering to natural laws.

Over the following century, significant advancements in understanding the brain were made, laying the groundwork for modern neuroscience. Four crucial insights emerged during the nineteenth century:

- Nerves as Wires

- The discovery of electricity’s role in nerve function replaced the outdated idea of fluid movement within nerves. Instead, nerves were understood as conduits for electrical signals to and from the brain.

- Localization of Specifi c Functions to Different Parts of the Brain

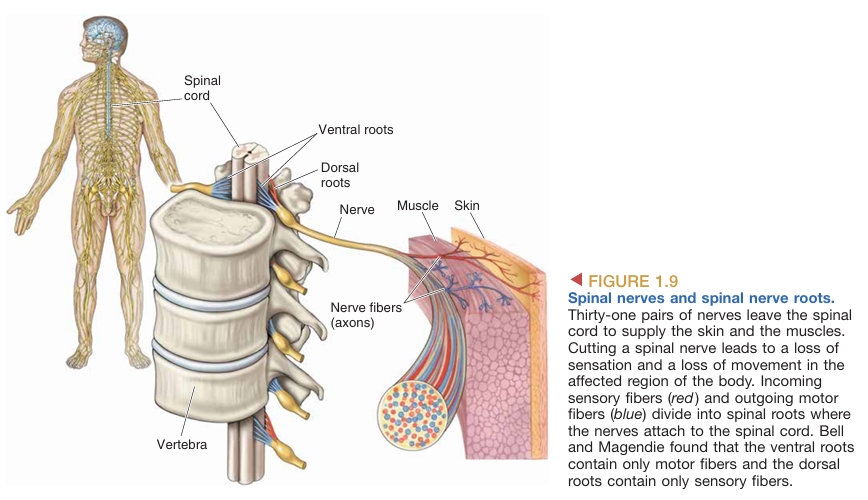

- Scientists like Charles Bell and François Magendie demonstrated that sensory and motor functions were separated within nerves, with different roots leading to distinct destinations in the spinal cord. Further experiments showed specific brain regions were responsible for different functions.

- The Evolution of Nervous Systems

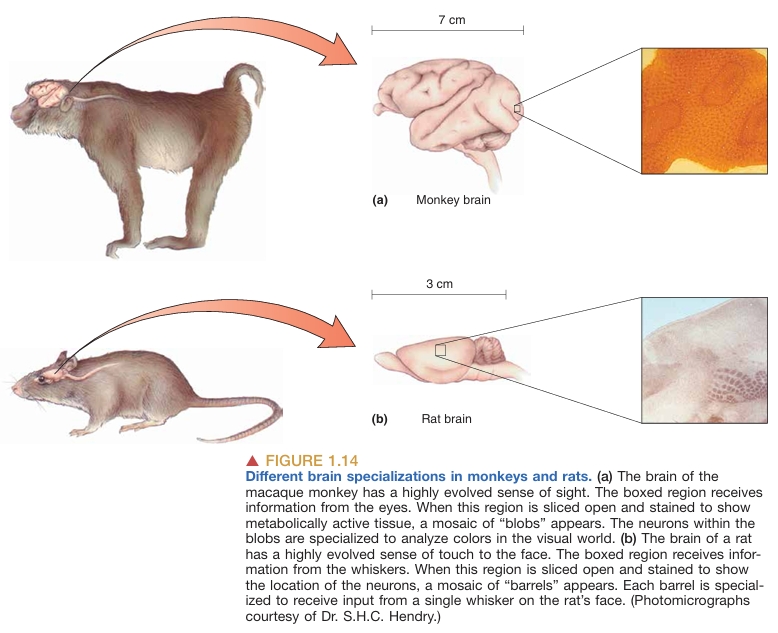

- Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection revolutionized biology, including the understanding of nervous systems. The idea that behavior could evolve led to the recognition that nervous systems of different species share common mechanisms, facilitating the use of animal models in neuroscience research.

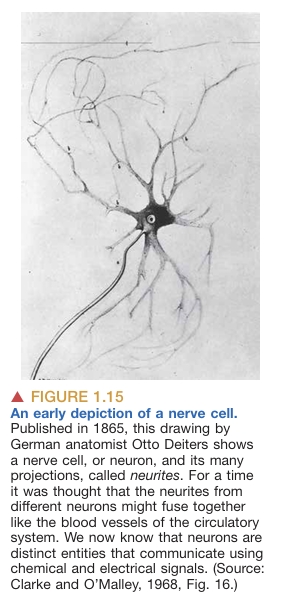

- The Neuron

- Lastly, technical advancements in microscopy during the early 1800s enabled the examination of brain tissues, leading to the recognition of cells as the basic units of tissue. By 1900, the neuron was identified as the fundamental functional unit of the nervous system.

NEUROSCIENCE TODAY

The history of modern neuroscience forms the foundation for this textbook, which aims to explore recent developments in the field. Brain research today is conducted across various levels of analysis, reflecting the complexity of understanding the brain.

Levels of Analysis

- Molecular Neuroscience: This level focuses on studying the brain’s intricate array of molecules, which play vital roles in communication between neurons, controlling neuron function, growth, and memory storage.

- Cellular Neuroscience: Moving up, cellular neuroscience examines how these molecules interact within neurons, influencing their properties, functions, connections, and developmental processes.

- How many different types of neurons are there?

- How do they differ in function?

- Systems Neuroscience: Neurons form circuits that underpin specific functions, like vision or movement. At this level, neuroscientists study how these neural circuits process sensory information, form perceptions, make decisions, and execute actions.

- Behavioral Neuroscience: Understanding how neural systems generate behavior is the focus here. Researchers investigate memory, the effects of drugs on mood and behavior, gender-specific behaviors, dream creation, and their neural correlates.

- Cognitive Neuroscience: This level explores the neural mechanisms underlying higher mental functions such as self-awareness, imagination, and language. It aims to understand how brain activity gives rise to complex cognitive processes, offering insights into the mind-brain relationship.

By breaking down the complexity of brain function into these distinct levels of analysis, neuroscientists can systematically investigate different aspects of brain function and behavior, advancing our understanding of the brain and its role in cognition and behavior.

Neuroscientists

Neuroscientists, much like rocket scientists, dedicate years of study to understanding the brain. Many start by assisting in research labs during or after college, then pursue a Ph.D. or M.D., followed by postdoctoral training before establishing their careers at universities, institutes, or hospitals.

Clinical Neuroscientists (M.D.s): Diagnose and treat neurological and psychiatric disorders. Specialties include:

Specialist Description Neurologists Treat nervous system diseases. Psychiatrists Focus on mood and behavior disorders. Neurosurgeons Perform brain and spinal surgeries. Neuropathologists Study nervous system diseases at the tissue level. Experimental Neuroscientists (M.D. or Ph.D.): Conduct research using various techniques:

Type Description Developmental neurobiologist Analyzes the development and maturation of the brain Molecular neurobiologist Uses the genetic material of neurons to understand the structure and function of brain molecules Neuroanatomist Studies the chemistry of the nervous system Neurochemist Study nervous system diseases at the tissue level Neuroethologist Studies the neural basis of species-specific animal behaviors in natural settings Neuropharmacologist Examines the effects of drugs on the nervous system Neurophysiologist Measures the electrical activity of the nervous system Physiological psychologist (biological psychologist, psychobiologist) Studies the biological basis of behavior Psychophysicist Quantitatively measures perceptual abilities Theoretical Neuroscientists: Use mathematical and computational models to analyze brain function, helping refine experiments and uncover fundamental principles of nervous system organization.

Neuroscience is highly interdisciplinary, requiring expertise in biology, chemistry, psychology, and mathematics to unravel the complexities of the brain.

The Scientific Process

Neuroscientists follow a structured scientific process to establish truths about the nervous system. This process consists of four essential steps: observation, replication, interpretation, and verification.

- Observation Observations arise from experiments designed to test hypotheses or from careful examination of the world, introspection, or clinical cases. For example, Bell tested the role of ventral roots in muscle control, while Broca linked left frontal lobe damage to speech loss.

- Replication To ensure reliability, observations must be replicated by repeating experiments on different subjects or making similar observations in different patients to rule out chance occurrences.

- Interpretation After confirming an observation, scientists interpret the results based on current knowledge and personal biases. However, interpretations may change over time as new information emerges. For instance, Flourens misinterpreted brain function due to limited knowledge and personal biases.

- Verification Verification ensures that independent scientists can reproduce the findings by following the original protocols. If results cannot be verified, inaccuracies or unrecognized variables may be at play. Successful verification establishes scientific facts, while failure prompts new interpretations.

Despite rare instances of scientific fraud driven by competitive pressures, the scientific process ensures that false observations are eventually exposed. The vast body of knowledge in neuroscience today underscores the importance of this rigorous method.

The Use of Animals in Neuroscience Research

Most knowledge about the nervous system comes from animal experiments, where animals are often sacrificed for neuroanatomical, neurophysiological, or neurochemical studies. This raises ethical concerns about the use of animals in research.

- The Animals Historically, humans have used animals for various purposes, including food, clothing, and companionship. The number of animals used in research is minimal compared to those used for other purposes, especially in neuroscience, where rodents like mice and rats are the most commonly studied species. The choice of species depends on the research question and its relevance to human biology.

- Animal Welfare Modern neuroscientists prioritize animal welfare, ensuring ethical treatment through specific moral responsibilities

- Using animals only in experiments that advance knowledge of the nervous system.

- Minimizing pain and distress with anesthetics and analgesics.

- Considering alternatives to animal use whenever possible. Compliance is monitored through Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC), peer review, and strict federal laws regulating animal care and housing.

- Animal Rights While most people support humane animal research, some activists argue for complete abolition, believing animals have the same rights as humans. This perspective raises ethical dilemmas

- Should medical advancements from animal research be rejected?

- Is animal control equivalent to human genocide?

Animal welfare should not be confused with animal rights. While activists have sometimes spread misinformation and resorted to vandalism, the importance of animal research in understanding and treating neurological disorders remains undeniable. Neuroscientists advocate for the responsible use of animals to advance medical knowledge and alleviate human suffering.

TABLE 1.3 Some Major Disorders of the Nervous System

| Disorder | Description |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | A progressive degenerative disease of the brain, characterized by dementia and always fatal |

| Autism | A disorder emerging in early childhood characterized by impairments in communication and social interactions, and restricted and repetitive behaviors |

| Cerebral palsy | A motor disorder caused by damage to the cerebrum before, during, or soon after birth |

| Depression | A serious disorder of mood, characterized by insomnia, loss of appetite, and feelings of dejection |

| Epilepsy | A condition characterized by periodic disturbances of brain electrical activity that can lead to seizures, loss of consciousness, and sensory disturbances |

| Multiple sclerosis | A progressive disease that affects nerve conduction, characterized by episodes of weakness, lack of coordination, and speech disturbance |

| Parkinson’s disease | A progressive disease of the brain that leads to difficulty in initiating voluntary movement |

| Schizophrenia | A severe psychotic illness characterized by delusions, hallucinations, and bizarre behavior |

| Spinal paralysis | A loss of feeling and movement caused by traumatic damage to the spinal cord |

| Stroke | A loss of brain function caused by disruption of the blood supply, usually leading to permanent sensory, motor, or cognitive deficit |

The Cost of Ignorance: Nervous System Disorders

Neuroscience research is expensive, but the cost of ignorance about brain disorders is far greater. Many families experience the impact of neurological diseases, which have severe personal and societal consequences.

- Neurodegenerative Disorders

- Alzheimer’s disease causes dementia, impairing memory and cognitive functions, and is always fatal. It affects over 4 million Americans, with an annual care cost exceeding $100 billion.

- Parkinson’s disease leads to a crippling loss of voluntary movement, affecting over 500,000 Americans.

- Mental Health Disorders

- Depression affects over 30 million Americans and is a leading cause of suicide (30,000 deaths annually).

- Schizophrenia causes delusions, hallucinations, and bizarre behavior, impacting over 2 million Americans.

- The combined cost of mental illnesses exceeds $150 billion annually.

- Other Major Disorders

- Stroke is the fourth leading cause of death, disabling over 500,000 people annually and costing $54 billion.

- Substance addiction costs over $600 billion yearly.

More Americans are hospitalized with neurological and mental disorders than any other major disease group. Beyond economic costs, the emotional toll on victims and families is devastating.

Neuroscience research has led to better treatments for disorders like Parkinson’s, depression, and schizophrenia. Ongoing studies aim to rescue dying neurons and understand addiction. Despite progress, much remains to be learned about the brain.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The historical foundations of neuroscience were built over generations, with modern researchers using advanced technologies to further our understanding of brain function. The insights gained from neuroscience research form the basis of this study.

Methods of Studying the Brain

- Behavioral observations help reveal brain function through external actions.

- Computer models simulate brain computations to understand cognitive processes.

- Brain wave measurements from the scalp provide insights into electrical activity during different states.

- Advanced imaging techniques allow for noninvasive study of brain structures and activity.

- Direct experimentation with brain tissue remains essential for understanding neural mechanisms at anatomical, physiological, and chemical levels.

Future of Neuroscience

The rapid pace of neuroscience research brings hope for new treatments for debilitating nervous system disorders. Despite significant progress, our understanding of brain function remains incomplete. However, this vast unknown makes neuroscience an exciting field, with groundbreaking discoveries always on the horizon.